Since the 14 th century, diamonds have been fashioned, set and worn in jewelry. As technology has improved over the centuries, the art of diamond cutting has grown more and more precise and sophisticated.

How a diamond is cut greatly impacts its sparkle, shine, and brilliance. Master cutters are trained to cut diamond rough to maximize both a diamond’s beauty and its marketability.

Where Did the Diamond Come From?

Diamonds were found in India in the 11 th century and were worn in jewelry as unpolished rough until diamond cutting began in the 14 th century. Since diamonds are so hard, they were essentially left in their natural crystal form with surface polishing.

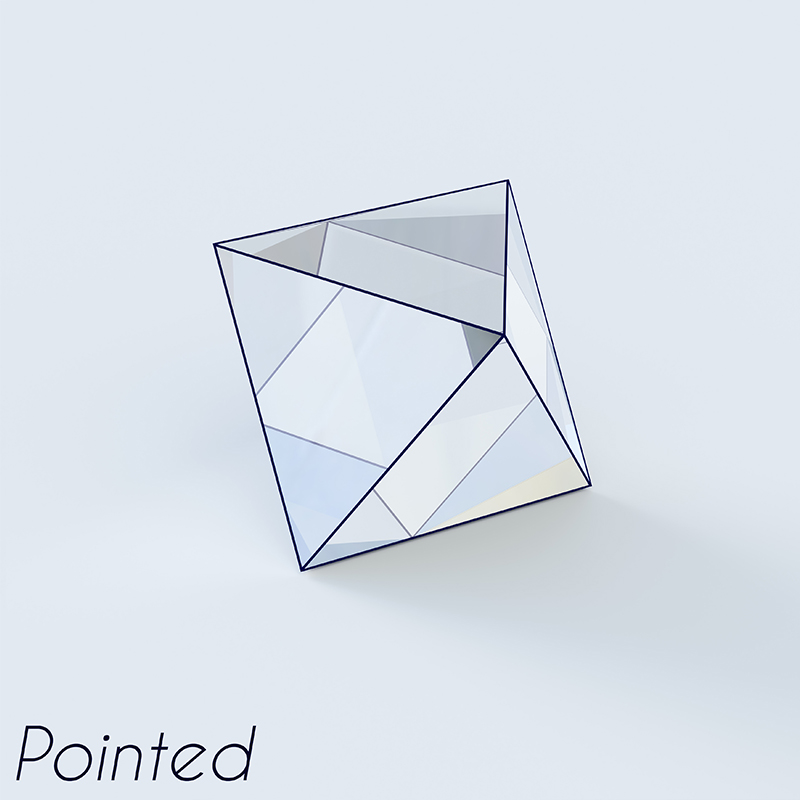

Point Cut Diamond

The Point Cut was the first cut to evolve, using a chisel to create a point at the center of a piece of rough diamond, close to its natural crystal octahedron shape. Cutters realized that their technique in cutting and polishing a diamond could accentuate a stone’s beauty.

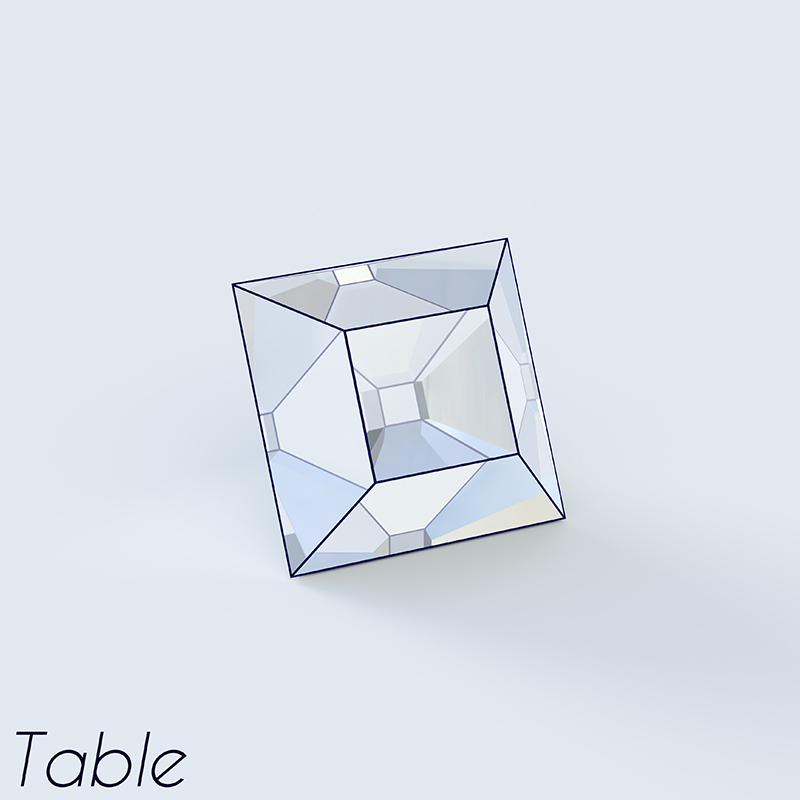

Table Cut Diamond

The Table Cut evolved from the Point cut in the 15 th century by cleaving off one of the pyramidal points of the Point cut to create a flat top – the table. The table facet greatly improved the beauty of the diamond, allowing more light to enter the stone, and thus, increasing its brilliance. The remaining point on the bottom of the diamond was flattened to create a culet, preventing breakage at a sharp point. As stone cutters experimented with different angles and proportions, they discovered that cutting facets above and below the girdle (edge of the stone) at around 45 degrees maximized light return.

In the 15 th century, rotary tools with diamond dust developed, allowing cutters to grind facets into diamonds with greater ease than ever before. By the early 16 th century, Portugal conquered the city of Goa, India, and established it as the center of diamond trading. Rough diamonds were exported to Europe. There cutting centers developed in Bruges, Paris, and Antwerp.

Diamond Cutting Industry Takes Off

By the 16 th century, the diamond-cutting industry had developed enough to move beyond the Point and Table cuts.

Cutting and faceting diamonds advanced. Creating new shapes and faceting styles. The first being the Rose Cut.

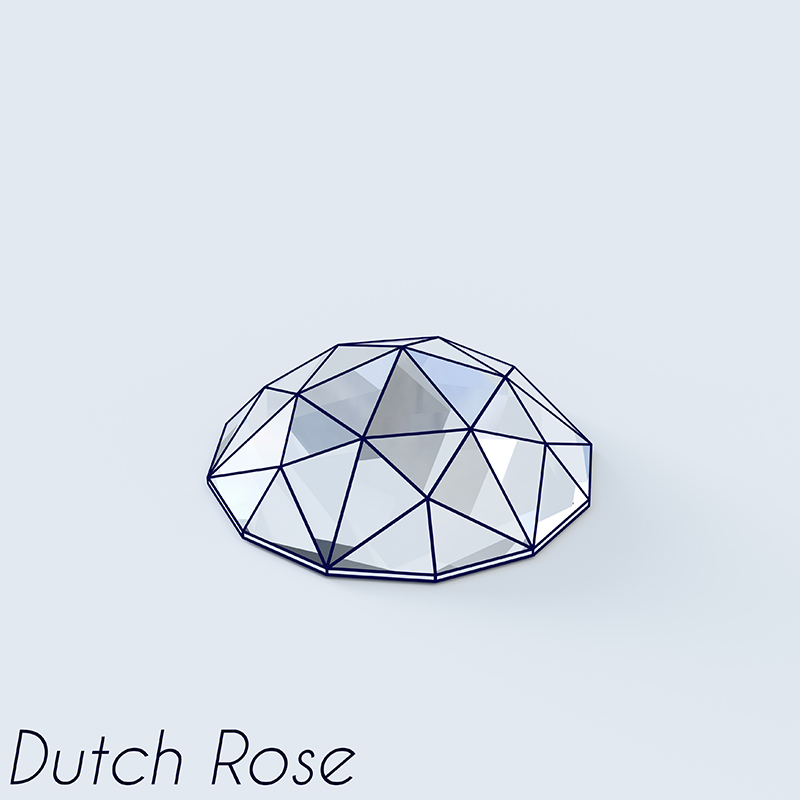

Rose Cut Diamonds

Rose cut diamonds are well suited for flatter diamond crystals. As they are cut with a flat bottom and rounded top with triangular facets. More facets on the surface of the diamond gave it more sparkle than ever before, perfect for glistening in candlelight. Their shallow depth also showed a larger surface area, giving a bigger, more sparkly appearance.

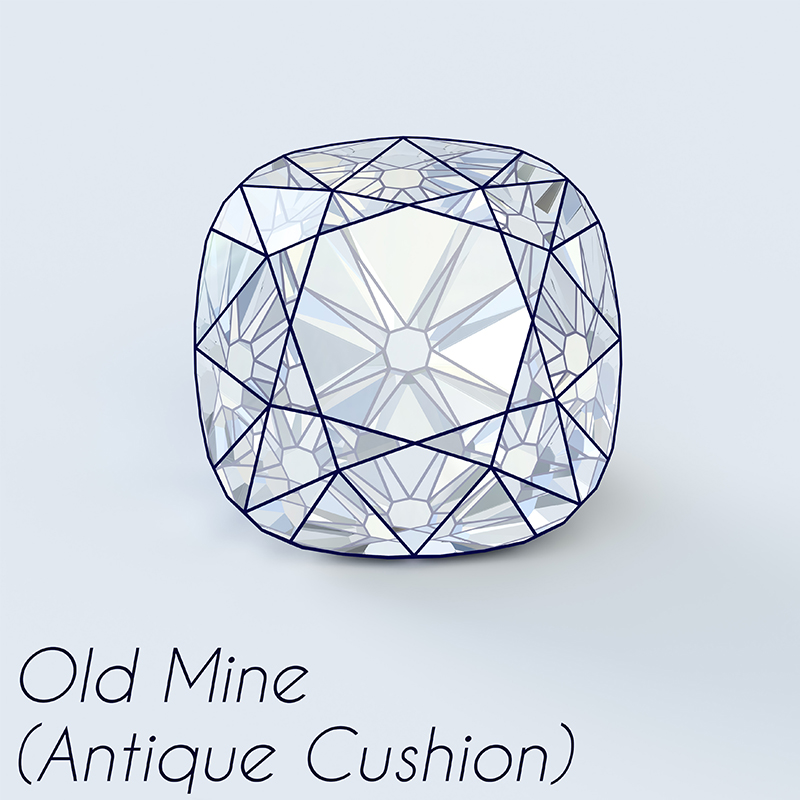

Old Mine Cut Diamonds

Developed in the 18 th century are the Old Mine Cut diamonds—to further enhance diamond brilliance. Old Mine cut diamonds were the beginning of the brilliant style. Cut with more facets on the top and bottom of the diamond, not just triangular facets in Rose cuts, but also rhombic, kite, and other geometric-shaped facets.

The perfect symmetry of the outline and facets were not possible, because they cut and polished by hand. The outline of Old Mine cut diamonds is irregular or cushion shaped.

Old European Cut Diamonds

Old European Cut diamonds developed by the late 19 th /early 20 th century. Henry D. Morse and Charles M. Field invented the bruting machine in the 1870s, which mechanized cutting the outline of the diamond. Thus using steam power until the first electric bruting machine was invented in 1891.

Therefore diamond outlines were shaped by machines with greater precision and accuracy for symmetry, allowing the facets to also be more precise and symmetrical. Old European cut diamonds are round in outline and have more regular faceting patterns than Old Mine cut diamonds. Table facets were now octagonal.

Transitional Cut Diamonds

Transitional Cut diamonds represent the transition from Old European cut diamonds to modern Round Brilliant cut diamonds in the early to mid-20 th century. Table facets became larger, they were cut shallower, and culets were smaller. Symmetry and facet cutting continued to become more sophisticated.

Round Brilliant Cut Diamonds

Today’s Round Brilliant Cut is very standardized as study continued in the ideal proportions to optimize light return and sparkle. The angles and proportions of the shape and facets are so precise that machines are programmed to cut them with lasers.

Fancy Cut Diamonds

Modern Fancy Cut diamonds are any shape other than a round brilliant. Examples of fancy brilliant cut stones are oval, pear, heart, princess and marquise cuts. The outline of these cuts are different than a round brilliant, but the cutting style is the same- a variety of facet shapes and standardized proportions designed to optimize the diamond’s brilliance.

Step Cut Diamonds

Other Fancy Cut diamonds are cut in a different style, called Step Cut. Examples of fancy step cut diamonds are emerald and baguette cuts. Instead of using a variety of different shaped facets across a stone’s surface, step cut facets run parallel to each other in tandem with the outline of the stone. Not as brilliant, they are simpler than brilliant cuts and elegantly display a stone’s clarity.

Diamond Cutting

Diamond cutting has become so precise and consistent that a system has developed to grade a diamond’s cut based on the proportions of the table facet, angles of the top and bottom facets, culet size and quality of polishing and finishing.

Round brilliant cut diamonds are the most standardized. Cutters found the best way to display a diamond’s brilliance. They have ideal proportions and number of facets, making them the most common cut.

Other cuts and fancy shapes have greater variations but are also graded on their proportions, polish, and finish.

Start the Appraisal Process

We’d love to work with you and appraise any diamond you have. Submit your jewelry on our website.

Authored by: Hana Thomson

Hana Thomson is a freelance jewelry writer and appraiser in the Ann Arbor area. She has worked at museums, auction houses and in jewelry retail and production. With a Master’s degree in History of Jewelry Design from 1850-1950 from Parsons/Cooper-Hewitt in NYC and a Graduate Gemologist degree from GIA, she loves continuing to learn and research the stories behind jewelry, watches, and objects.